If a test falls in a forest...

The saying goes "If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?" I have similar question that shapes the way I think about software testing: If a test is performed but no one takes action on the results, should I have performed it? I think not.

If the answer to "Who cares?" is "No one," don't perform that test. If you're not going to take action on the results of your testing in the coming hours, days, or weeks, don't perform that test. The world around you will change in the meantime, and the old results will not be as valuable.

One of the 12 Agile Principles is simplicity, or maximizing the work not done. Testing on an agile team provides information to help decide what work should picked up in the coming iteration(s). But without meaningful collaboration or feedback, testing is a pile of work for no reason. Work is not meant to produce waste. Save your time and your sanity by thoughtfully analyzing what should not be done, and coming to an agreement with your team about it.

My team gets scared about the quality of our product and skeptical about how I'm using my time when I describe what I'm not testing, or which automated tests I'm not going to run. "But isn't testing your job?" says the look on their faces. "But then what are you going to do?" is what they manage to say. Rather than capitulating for appearances, to just "look busy," I take this as a challenge to make my exploratory testing and other work I'm doing for the team more visible.

Risk-based testing

In her TestBash Home talk, Nishi Grover Garg asked us to think about estimating impact and likelihood (with possible home intruders as an example). I'd have trouble pinning down our no-estimates team on concrete numbers for undesireable software behavior.

Slide from Nishi's TestBash Home talk

Slide from Nishi's TestBash Home talk

But it does reflect the conversations Fiona Charles's test strategy workshop encouraged me to spark on my team. We do talk about "Yes, this would be a problem, but customers can use this work-around." Or "Yes, we could dive in and investigate whether than could ever happen, but is that more important than picking up the next story?" Being able to identify risks and have thoughtful conversations about their threat to stakeholders allows us to make informed decisions about how we should be spending our time. In testing, we don't always want the most information, we want to discover the best information about the product as efficiently as we can.

Examples from my current project

Cross-browser testing

We were preparing our web application for a big marketing presentation. The presenter had Firefox as the default browser on their PC. We had a script of the actions they'd perform on stage, and which pages the audience would see. I happened to find bugs on pages we weren't showing, or in the way the scroll bars behaved in Chrome rather than Firefox on my Mac.

I did not add these issues as bugs in our tracking system, or dig into them further. I knew that they did not pose a risk for the presentation, and a new design would be coming along before customers would potentially use those pages in Chrome on a Mac.s

The pipeline

We have a pipeline. It runs the tests we've automated at the API and the browser levels against the build in our test environment. I hoped it would inspire the team to think about what the next step could be: getting the tests to run against before merging into our main line, setting up an environment where we're not dependent on the (shared) test environment, looking at the results to see where our application or tests need to change.

But we don't look at the results. We don't have alerts, we don't open the page during standup, we don't use them as a reference when we're debugging, we don't have a habit of looking at the results. If we do happen to look at the results, we don't take action on it. Building the stability of our feedback loop is not seen as high-priority a task as building new features.

We don't need to run this pipeline. It's using up AWS resources. Looking at the long line of red X's on the results page only provides alert fatigue. We would be better served by not running these tests.

Minimum viable deadline

We promised to deliver a feature to a dependent team by a sadline. (A sadline is a deadline without consequences.) In the week before the sadline, three stories were left. On the first story, I found a mistake the developer declared "superficial" when he was lamenting our lack of deep testing. He decided to review the automated tests I'd written for the second story. He found a couple of use-cases that would require a very particular set of circumstances to occur. I wanted to encourage the behavior of reviewing the tests and thinking about what they're doing more deeply, so I spent the last hour and a half before a holiday weekend automating these two cases.

I'd drafted some basic automated tests for the third story, but the last feature went relatively unexplored. I should have used my scant time to test the third story more thoroughly instead. The complicated tests for the second story could have waited until next week. While we would be curious about the results, it would not have stopped our delivery of the feature. I should not have written them.

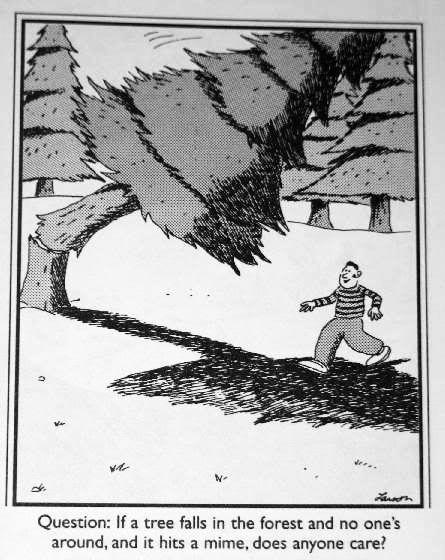

Far Side cartoon

Far Side cartoon

You may be scared to say no to testing things that don't matter, where the performance will not reveal any risks or cause any follow-up actions to take place. It may be tempting to spend a bunch of time testing all the things you can think of, and only reporting on the tests that yield meaningful results.

But life is not about keeping busy. Make your time at work meaningful by executing meaningful work and declining to do things that aren't important right now.